Q&A

John Hinckley Jr. speaks: ‘I’m trying to not dwell on the past’

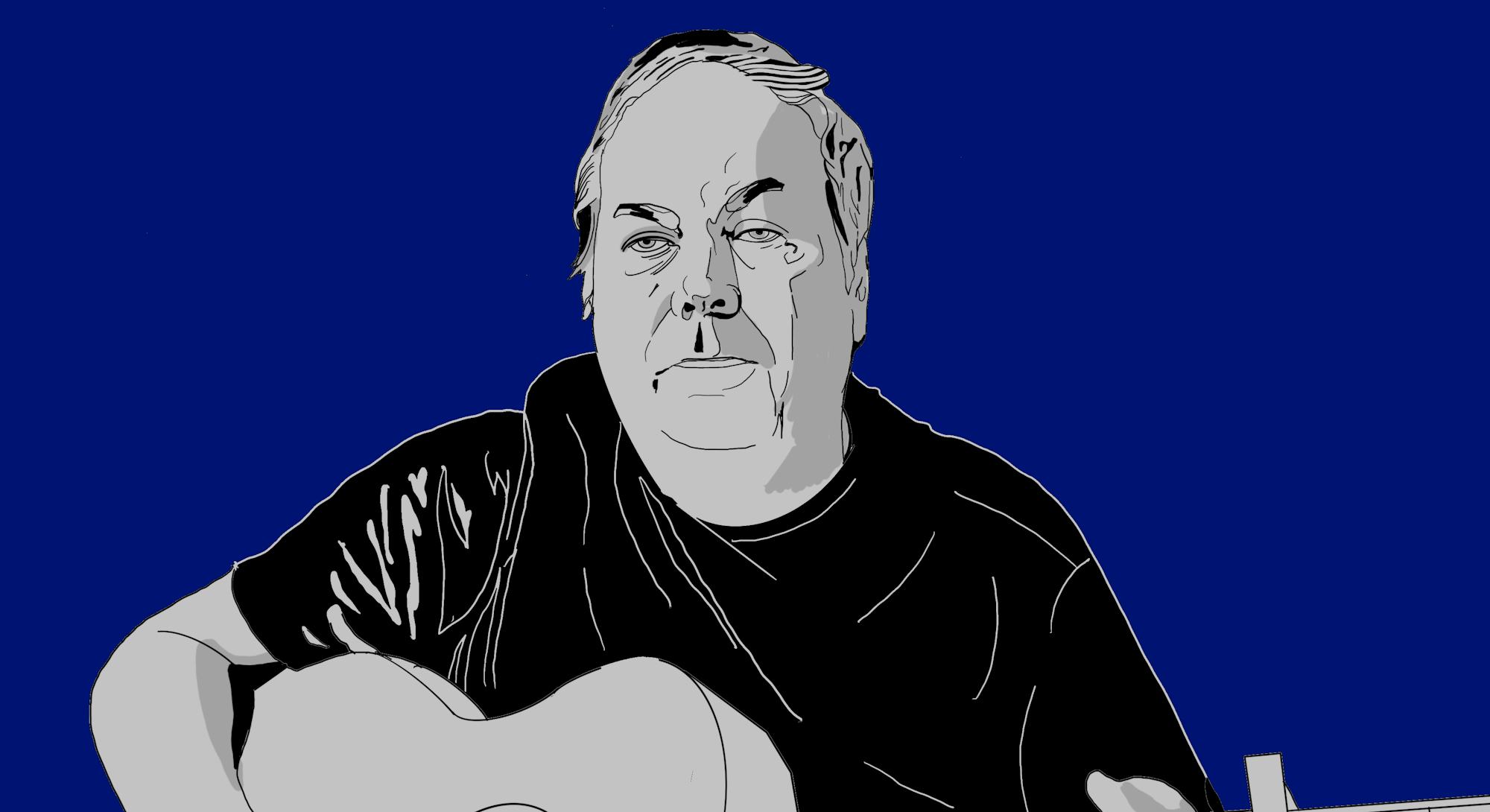

The man who shot Reagan is now totally free. He talks about his music career and the concept of redemption with Eve 6 frontman Max Collins.

Last Wednesday, John Hinckley Jr. — the man who shot President Ronald Reagan in 1981 and was found not guilty by reason of insanity — was released from all court restrictions, meaning he has no more government oversight.

“After 41 years 2 months and 15 days, FREEDOM AT LAST!!!” he tweeted early that afternoon.

But that day it wasn’t all good news for the 67-year-old Hinckley, who is trying to get a music career off the ground. Later, Brooklyn music venue Market Hotel announced on social media that it was canceling a sold-out July concert by Hinckley due to safety concerns.

“There was a time when a place could host a thing like this, maybe a little offensive, and the reaction would be ‘It’s just a guy playing a show, who does it hurt — it’s a free country.’ We aren’t living in that kind of free country anymore, for better or worse,” read the venue’s statement.

It concluded, “It is not worth the gamble on the safety of our vulnerable communities to give a guy a microphone and a paycheck from his art who hasn’t had to earn it, who we don’t care about on an artistic level, and who upsets people in a dangerously radicalized, reactionary climate.”

Hinckley says he understands the move to a degree, but he’s feeling deflated. “Boy, that really was disappointing,” he tells Input, “because I’ve had that [concert] on my mind since about April, when we set this thing up.” It was the third of the controversial figure’s three announced shows to be canceled, after gigs in Chicago and Hamden, Connecticut were nixed. Hinckley has no other dates scheduled for what he’s dubbed his Redemption Tour.

The Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation and Institute said in a statement earlier this month that the organization was “saddened and concerned that John Hinckley Jr. will soon be unconditionally released and intends to pursue a music career for profit.”

In 1982, a jury acquitted Hinckley in the shootings of then President Reagan, White House secretary James S. Brady, and two others outside a Washington, D.C. hotel. (Brady was gravely wounded and ultimately died of his injuries in 2014; the medical examiner’s office ruled it a homicide, but no new criminal charges were brought.)

Having been found legally insane, Hinckley — who said that he tried kill the president to impress actor Jodie Foster — went on to spend more than three decades in a psychiatric hospital in D.C.

In 2016, Hinckley was granted conditional release, moving to Williamsburg, Virginia, where he still lives. Two years later, a federal judge ruled that Hinckley — who had been posting his music online anonymously — could begin publicly releasing his music, artwork, and writings under his own name. He subsequently started putting his song performances on YouTube, where he now has nearly 29,000 subscribers. (His songs are also on Spotify and other music streaming services.)

In September 2021, a federal judge approved Hinckley’s June 15, 2022 unconditional release date. The month after that ruling, Hinckley joined Twitter, where he currently has more than 36,000 followers. (He doesn’t follow anyone.) Early on, Hinckley tweeted names of some of the musical artists he was listening to:

Upon seeing mention of his band, Max Collins, the terminally online lead singer of Eve 6 (and now Input’s advice columnist), tweeted a reply: “lets do a song together john.” That collaboration has yet to happen, but on Friday, Collins and Input features editor Mark Yarm did manage to snag Hinckley for a three-way phone call to discuss his music career and, with great reluctance on his part, his notorious past.

The following — the most substantial interview with Hinckley to be published since the 1980s — has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Input: Max, you told me that you’re genuinely a fan of John’s music. What is it about it that appeals to you?

Max Collins: There’s a through line of hope to John’s songs. Which it is difficult to do. At least in a way that reaches me, because oftentimes songs that are too positive or too hopeful lack credibility to me — I don’t necessarily believe the singer. But with John’s songs, there’s a sadness about them, too. There’s a sadness and a kind of longing that amplifies and gives authenticity to the hopeful sentiment. I believe him when he’s singing about this stuff, and the positive stuff — the hope stuff — feels like it was hard-won for him.

They’re simple songs. It’s language-of-the-heart stuff, but it’s deeply, deeply resonant to me personally. I find myself relating to them and considering my own dark nights of the soul and sort of clinging to this aspirational notion of hope. And I feel like that’s what John does in his writing, and correct me if I’m wrong, John?

Hinckley: You’re correct. Anyone who’s heard my songs knows that they are trying to be kind of upbeat and inspirational, because when I listen to bands like Nirvana or something like that, where there’s just so much angst going on in the song, I really don’t want to hear that too much. ’Cause that just kind of brings me down. So I like songs that are more positive.

Collins: It sounds like you’re talking about that kind of Beatles tradition a little bit, where it’s, like, peace and love —

Hinckley: I don’t know how old you guys are, but I’m probably quite a bit older. And I grew up with the Beatles. So I’m a ’60s guy. And the music I listen to to this day is ’60s rock and roll. [I listen to] most of the Beatles songs, especially the earlier songs — the pop songs, the upbeat love songs. And that’s kind of how I learned how to write a song that way. And I’m still doing it today.

Collins: When did you start writing songs?

Hinckley: I can’t give you the exact year, but it was when I was a teenager.

Collins: And did you teach yourself to play guitar?

Hinckley: Yes, I did. I took about eight lessons. But I taught myself the chords and what I needed to know to adequately play the guitar and write a song.

Collins: And one more kind of nerdy question: What kind of acoustic guitar do you play?

Hinckley: It’s a Fender acoustic electric. It’s not a great guitar, but I like the feel of it. It’s decent.

Collins: What is your songwriting process? Do you start with a lyric and melody idea first? Do you have a holistic lyrical concept before you start writing?

Hinckley: No, no, no, no. I just pick up a guitar and just start strumming chords, and in my head, I come up with a melody. So it’s always melody first. Every song. Every song of mine is melody first. And when I get the melody down, then I sit down and write out the lyrics.

“I’m as free as you or anybody else in the world now. And yeah, that makes me very happy.”

Collins: Yeah, I do the same thing. I start to find a simple progression, basically start making sounds with my mouth.

Hinckley: That’s what I do.

Collins: And wait till something feels kind of compelling. And then plug words into that. And I’m perfectly happy sacrificing words to make them fit a melody. I think that’s what a lot of people who have never written songs and think of it as poetry misunderstand. The lyrics are important, but if they don’t work with the melody, it’s nothing. Melody and the rhythmic scan of the words take precedence for me as well.

Hinckley: Well, you know, besides the Beatles, I’ve been a huge fan of Bob Dylan’s all my life. And his first five or six albums to me are just classic. I still listen to them a lot these days. So a lot of my songwriting technique and wording comes from Bob Dylan, too.

Input: What else are you listening to, John? You seem to have some pretty contemporary taste as well.

Hinckley: Well, I don’t, to be honest. I got into some bands in the ’90s. Neutral Milk Hotel’s In the Aeroplane Over the Sea is probably my all-time favorite album. I like Magnetic Fields, Stephin Merritt, and some of that Sebadoh — that’s pretty good stuff. But when I’m driving around, I’m not listening to Top 40 radio. I just don’t like it at all. I’m probably listening to CDs in my car. You know, the older stuff.

Collins: I love the way your records sound, and the players that you have playing with you when you do have accompaniment, their choices are really tasteful and cool. I was curious: Who produces your music? Who plays in your band? And how did you meet these people?

Hinckley: I did the whole thing. I’m a one-man band. On all the songs on Spotify, there’s only two songs where another guy is helping me out, but all the rest of them I do all the instruments and vocals and everything.

Collins: As I said earlier, your songs tend to be uplifting, but there’s a sadness in them, too. That has the effect of amplifying the joy, because it feels hard-won. I guess my first question is, is this happiness that you are experiencing now? Or are you aspiring to happiness in your songs? If you are happy now, how did you get there? How did you learn to be happy?

Hinckley: [Laughs.] How did I learn to be happy? Well, I don’t know how much you know of my whole life story. But just a couple of days ago, I got what’s called an unconditional release, meaning I have no ties to any court system. And I’m as free as you or anybody else in the world now. And yeah, that makes me very happy.

“And let me tell you, that’ll take a lot out of you to be an inpatient in a mental hospital for 35 years.”

The older songs, I’m probably aspiring to be happy. But on a lot of the newer songs I’m already happy. I’ve been living here in Williamsburg, Virginia, full-time since 2016. And I’ve been a happy guy since then. So I think that comes out in my songs.

But if you hear a tinge of sadness, it’s because I did 35 years in a mental hospital. And let me tell you, that’ll take a lot out of you to be an inpatient in a mental hospital for 35 years. It takes a lot out of you spiritually, physically, emotionally. So if you’re hearing a tinge of sadness in the songs, it’s probably from that. But as I said, for the past five or six years, I’ve been free, and, yeah, that’s where the happiness comes in.

Input: Now that you are fully free, what does a typical day in the life of John Hinckley Jr. look like?

Hinckley: I just do a lot of music still. I’m an artist. I do paintings and sell my paintings. I’m trying to get back into that a little bit, because for the past few months I was really focused on this concert in Brooklyn. And it fell through.

Input: What did you make of their explanation for why they pulled the plug? The venue cited “a dangerously radicalized, reactionary climate.”

Hinckley: Well, I agree with them to the extent that America right now is kind of scary with all the mass shootings going on and everything. You know, I watch the news like everybody else. I know what’s going on. And I was speaking to the promoter on a regular basis about security for the concert. I wasn’t taking it lightly by any means.

In fact, I was the one who was being the strong one, just saying, “Look, you’ve got to have extra security at this concert. It’s not just another typical concert.” And the promoter was agreeing with me on this. He was saying we’d have beefed-up security. So we were working on that up until Wednesday, when Market Hotel backed down.

Input: Are you fearing for your own life or the lives of people in the audience? What are your security concerns?

Hinckley: I wanted me to be secure, and I wanted the audience to be secure, too. I wanted that venue, Market Hotel, to be a secure environment the night of that show, and the promoter was agreeing with me on this. But Market Hotel is now saying it was just too much risk.

Input: Max told me that he had tried to set up an Eve 6–John Hinckley show in California and had trouble doing it. Max, you want to tell John what happened?

Collins: Yeah, I spoke to [Hinckley’s manager] Alina, and she said she didn't have connections with L.A. promoters and stuff. She said she was interested in maybe the Moroccan Lounge and asked if I had any connections there. So I reached out to my agent, who reached out to them. And they declined, as did a couple other similar-sized venues. Which is so cowardly to me, if I may editorialize for a second.

I guess the question attendant to that is, do you think the public at large will ever see you, John Hinckley, as a whole human being and accept you as an artist? Do you see the public perception of you being fixed or being changeable?

Hinckley: Well, I have a fanbase. I’d say about 99 percent of my fanbase are very young, like in their early twenties. So I do have a fanbase who likes my music a lot. And so we get these concerts set up, like in Chicago. We were selling tickets. And then the guy who owned the auditorium caught wind of it and backed out. There was a cancelation.

The same thing happened in Connecticut. We were selling tickets. Everything was going fine. And there was some local backlash, and the venue pulled out. Brooklyn is the third one that’s pulled out. And I’m starting to wonder if we’re going to be able to find venues that will stand by me and go ahead with the concert.

“I’m trying to get away from the image that I have in the public, that negative image. I’m not that person anymore. At all.”

Input: Do you understand the reluctance?

Hinckley: I do, and I don’t. As I said to you earlier on this call, I take my security very seriously. So I’m not going to do a concert if the venue is not secure. So I think in Chicago and Connecticut, if we could have come to an agreement that the venues were secure, I think the concerts should have gone on.

Input: But do you think it’s also people objecting to you being the man who shot Reagan and others? “Do we owe him a second chance?”

Hinckley: Well, I don’t know. That’s on them to decide that. I can’t make them change their mind as to what they think about me. But I’m trying to establish myself as a singer-songwriter and also an artist.

Collins: This sort of brings me to something that I’ve wrestled with myself. I’m a sober alcoholic, John. I’ve been sober for 16 years. You were calling your tour the Redemption Tour. And I have been curious about redemption as a concept. Just for myself. What does it mean to be redeemed? Does the public need to perceive you as being redeemed for you to be redeemed?

Hinckley: I mean, to be redeemed is internal — it’s not what somebody down the street thinks. But I just thought that was a good name for the tour: the Redemption Tour. Because I’m trying to get away from the image that I have in the public, that negative image. I’m not that person anymore. At all. And I’m trying to show them that I’ve redeemed myself through my music and art.

Collins: There’s an inherent generosity to art, I think. You’re sharing something about yourself. In your songs, you share the shadows and light. Do you feel like along with the other work that you've done — the inside work — that you can redeem yourself through art?

Hinckley: Yes. The answer is yes.

Input: Can you expand on that?

Hinckley: I tell people, “If you want to get to know me, listen to my songs.” You know, I sometimes don’t express myself that well just speaking. And maybe I come off as aloof to some people, and I don’t mean to be. But if they listen to my songs, they’ll see that I’m a caring person who has a lot of feelings and has a lot of hope and aspirations. In a lot of ways, I’m just like them, the person that’s listening to the song.

Input: My question is, do you feel you can be redeemed for shooting Reagan and the others 41 years ago?

Hinckley: I’m not sure if “redeemed” is the right word. But, you know, I want to kind of keep this to the music, if you don’t mind, and not go back to all that.

Input: No, I understand that. It’s just that obviously that’s what you’re known for, and people are going to want to know about it. Is there a statement you want to make about that?

Hinckley: You know, a lot of the interviewers, they do this. They say, “Oh, we’ll just talk about the music.” And they veer off into things from the past, and I’m trying not to do that. I’m trying to not dwell on the past.

The other thing is, I need to kind of get going with what I need to do. So if we can kind of wrap it up pretty soon?

“I’m looking for a legit record label to be on. That’s my dream.”

Input: Okay. Beyond actually getting to play some shows someday, what are your goals musically speaking?

Hinckley: I’m going to keep posting songs on Spotify and the other sites. I like doing that. I have a YouTube channel, and I posted about 31 videos. But I don’t think I’ve posted a video for about five months. So I want to get back into posting videos on my channel on YouTube.

My lifelong dream is to be on vinyl. I want to put out a vinyl album of my songs. I’ve had some record labels make offers to me. But I don’t like their offers. So I’m looking for a legit record label to be on. That’s my dream.

Collins: I would think that would be totally in the cards for you. And I hope it happens so I can get one. So this will be our last question here: Beyond music stuff, do you have any other goals now that you’re free and you can do whatever you want?

Hinckley: With the pandemic and restrictions I had on my travel, I wasn’t able to travel very much. So I do want to do some traveling. But my focus is mainly on the music and the art right now. And that’s kind of what takes up my day. It’s kind of where my interests are. So for at least the near future, that’s what I’ll keep doing.