Monkey business

These adorable baby ape NFTs? They’re racist — and stolen.

The scammy saga of the multimillion-dollar Lil Baby Ape Club shows that the digital art market is broken.

The NFT world is a messy space. It’s full of projects that are created and backed by a cadre of pseudonymous characters and are capable of soaring and sinking in the blink of an eye.

And one of the most complicated and confusing projects of all involves a collection of preschool primates.

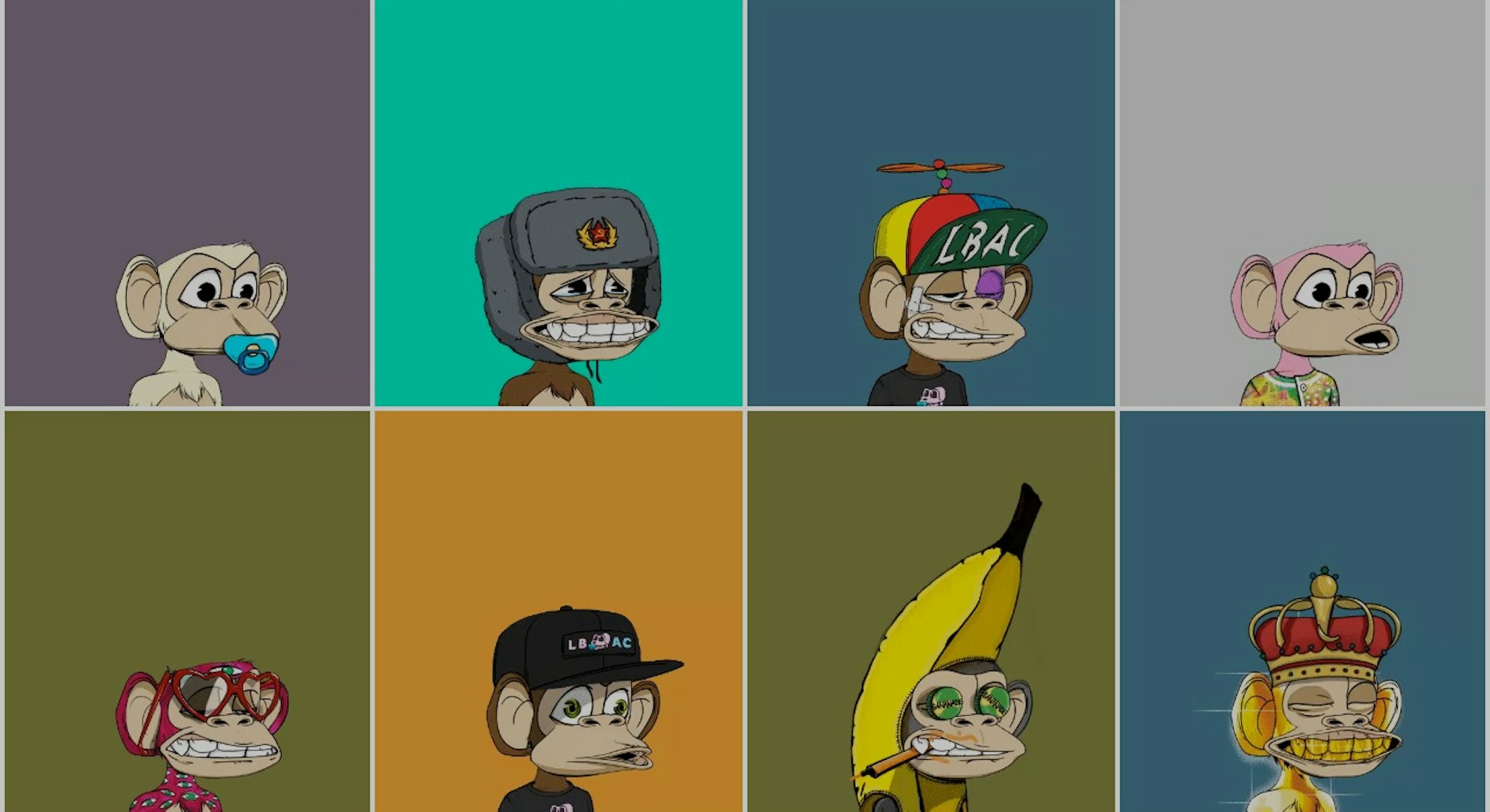

Lil Baby Ape Club is the brainchild of a group of three Russian NFT creators, brought to life on November 8. Set to formally launch tomorrow, Lil Baby Ape Club is an unofficial derivative of the insanely popular Bored Ape Yacht Club, a collection of 10,000 cartoon primates. But four days after the Russian creators published their project onto the blockchain, a second project, also named Lil Baby Ape Club, was launched.

Both projects share the exact same artwork across their 5,000 apes, according to a forensic investigation by a 25-year-old Canadian NFT collector who goes by the name Roh.

When Roh first came across the second Lil Baby Ape Club, he didn’t realize that it was a carbon copy of an original project. “I resonated with the art in a weird way,” he says, and decided to buy three baby apes of his own. The following day, while in the copycat community’s Discord, he saw a post appear from the original creators of Lil Baby Ape Club in which they claimed they had been ripped off.

“It was pretty clear that the art had basically been stolen.”

The message was swiftly deleted — Roh believes within 30 seconds or so — but before it disappeared, he managed to click a link taking him to evidence showing the original team had generated their NFT contract first. He connected with the Russian originators and began talking to them. “At that point, it was pretty clear that the art had basically been stolen,” he says.

It appears that the scammers managed to lift everything about the original project and launch it into the world earlier, and with a higher-profile campaign. (The original creators of the Lil Baby Ape Club repeatedly declined to speak with Input over the course of several days, citing a lack of time to talk. The alleged copycats, whose background is unknown, also did not respond to repeated requests for comment.)

The ersatz Lil Baby Ape Club collection became one of the buzziest NFT projects of the year. Around 3,000 people now own the 5,000 copycat baby apes that managed to launch first. The total volume traded is 3,888 ETH ($16.5 million). But alongside the questions about the clone project’s originality came scrutiny of the artwork itself.

A number of the apes use questionable iconography, including some wearing German flag suspenders and a white T-shirt emblazoned with “Monkey Pride.” Those NFTS have what the project’s founders call a “skinhead” characteristic.

Another NFT in the collection, given the name jam boy, echoes a racist term with connections to slavery in the British Empire.

“Being on the creator side, I know full well that traits don't ‘accidentally’ make it through,” says Joe Payne, an NFT collector and creator from Bentonville, Arkansas. who called out the issues with the community on Twitter when the ersatz LBAC first surfaced. And even if the creators plead ignorance, that’s no excuse, he says. “If that is happening, it’s just another sign that it’s a cash grab and not a thoughtful endeavor.”

The attention on the project turned up the heat on the copycat creators, who ended up apologizing for not spotting the troublesome presentation of stereotypes when they received the artwork. “This is something I clearly passed when checking the designs after being sent to me,” they said via Discord.

Despite the fact that the copycat Lil Baby Ape Club allegedly constitutes wholesale theft and is racist, the project remains on NFT marketplace OpenSea. In fact, it’s one of the platform’s Top 10 projects. OpenSea ignored repeated requests for comment from Input.

Unsafe space

This is, disappointingly, not the first time that NFT projects have been shown to have a serious issue with racism. Jungle Freaks, a collection of artwork by former Hustler artist George Trosley, was derailed after people pointed to his problematic previous work and suggested a fictional NFT world in which zombie generals wearing Nazi-esque outfits shoot gorillas might be less innocuous than first thought.

“I was disgusted and disappointed to hear [of Lil Baby Ape Club], but not shocked given that we’ve seen overt racism and discrimination in other NFT projects — Jungle Freaks being the most recent,” says Kristina Flynn, an NFT collector, consultant, and community leader spearheading diversity in the NFT world.

It’s an issue borne out of the lack of representation across the wider NFT community, believes Flynn. “The space is dominated by white, cis, straight men,” she asserts, citing reports that a minuscule proportion of the sector are women. “Many underrepresented communities — women, nonbinary, Black, brown, indigenous, LGBTQ2IA, neurodiverse, and folks with disabilities — don't feel safe and welcomed within the broader ecosystem and micro-communities that exist.”

“One of the inherent traits of decentralization is that no one can tell us what is or isn’t allowed.”

While it would be easy to think of the original creators of the project as the blameless victims, they did develop the original artwork that highlighted racist tropes. The Russian developers, however, told Roh that in Russia, “skinhead” wasn’t a racially charged term in the same way it is in the English-speaking world. “I don’t have any knowledge of if it’s true or not, because I don't understand Russian culture or what works there,” he says.

The original developers’ excuse seems inadequate: Russia has a vibrant racist and nationalist far-right community. “In the mid-1990s, a diverse right-wing movement came on the scene in cities such as Moscow, Voronezh, Riazan, Tiumen, Rostov-on-Don, and St. Petersburg,” says Eugene M. Avrutin, author of the upcoming book Racism in Modern Russia: From the Romanovs to Putin. “By 2007, Russia was home to some 60,000 to 65,000 skinheads.”

Russia, he adds, struggles with “white power extremists who organize training camps and knife-fighting sessions, with the explicit goal of preserving the white Russian nation from foreigners and dark-skinned minorities.”

Even setting aside the issues around hateful imagery, the original developers themselves seemingly aren’t blameless. “I personally believe both projects are scams,” says Kwen Lee, an NFT collector and industry observer who has tracked the crypto wallet of one of the creators of the original Lil Baby Ape Club and its transactions. Lee alleges that said creator was behind a prior scam NFT project called CryptoNuggets.

CryptoNuggets launched in late August under the control of a pseudonymous creator, Kakashi Nakamoto. It was a collection of 3,000 McNugget-style NFTs, with customizable sauces and toothpicks. But, claims Lee, the project came to naught, and Nakamoto escaped with 12 ETH — or nearly $50,000 — of investors’ money.

“The owner said he didn’t make any promises, so it was okay to make 12 ETH in sales, ignore people for months trying to contact him, and leave that project to die,” says Lee.

The whole sorry mess demonstrates the fundamental flaw with NFTs, which is simultaneously their greatest strength, says collector and creator Payne. “One of the inherent traits of decentralization is that no one can tell us what is or isn’t allowed,” he says. “It becomes about what the market will tolerate.

“As long as people are willing to throw money at things without understanding them,” he adds, “there will be people putting out things like Lil Baby Ape Club to profit from them.”