Culture

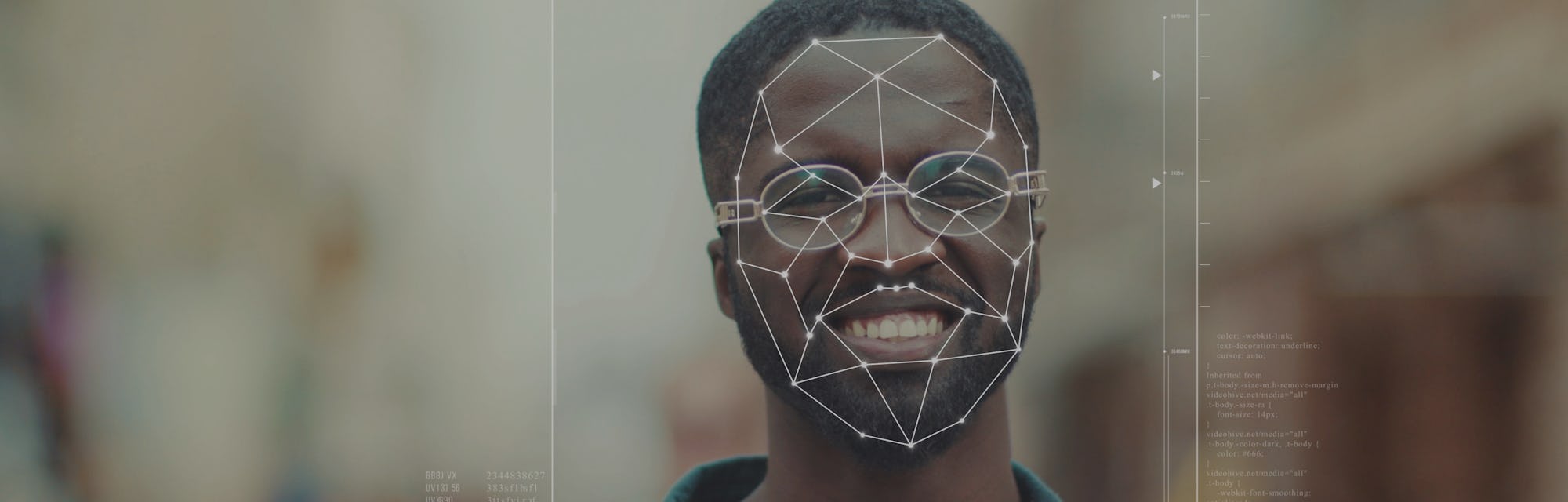

AI researchers tried to gauge 'trust' by looking at faces. Surprise: it's racist.

The paper has been slammed by computer engineers, art historians, and anyone who isn't a fan of phrenology-adjacent studies.

A recent study published in Nature Communications has garnered significant controversy for its uncomfortable proximity to the debunked and unethical concept of phrenology. Titled as "Tracking historical changes in trustworthiness using machine learning analyses of facial cues in paintings," the authors of the study — Lou Safra, Coralie Chevallier, Julie Grezes, and Nicholas Baumard — relied on machine learning to essentially inform them of faces that either looked trustworthy or didn't. The authors used portraits from the National Portrait Gallery, Web Gallery of Art, and regular selfies from the internet with several non-European photos in the mix.

They found that, "Trustworthiness in portraits increased over the period 1500–2000 paralleling the decline of interpersonal violence and the rise of democratic values observed in Western Europe. Further analyses suggest that this rise of trustworthiness displays is associated with increased living standards."

However, dozens of people — including computer engineers and art historians — have fiercely lambasted the study for its ethically unsound nature. Despite it not being outright phrenology, the paper ends up — whether its authors intended this or not — reincarnating a discredited approach to assessing trust based on facial structure, which is a dark history riddled with vitriolic discrimination against non-white racial minorities in particular.

The glaring flaws — The Nature paper isn't the only study to push phrenological-adjacent findings on readers. A separate paper by another team erroneously assumed that artificial intelligence could "predict" criminality in a person by simply viewing photos. Throughout the history of science as well as different cultures, some researchers have attempted to present the human face as an adequate canvas for social trust. But social trust is an incredibly — and at times, frustratingly — abstract and elusive concept.

An algorithm cannot define social trust, much less spot it, as it works with data and training material provided by humans. And with those humans, there comes bias and preconceived notions about facial trustworthiness.

As critics noticed with this study, the paper fails to factor in racial differences, how people of color — particularly of darker complexions — are frequently de facto viewed suspiciously, how gender affects this study (authors note that a feminine face is considered more trustworthy than a masculine structure), how individuals with autism showing flat or blunt effect would be incorrectly viewed as lacking "social openness" by the algorithm, and more.

There is nothing verboten about scholarly inquiry, including studies on controversial subject matter. It should be encouraged and nourished in academic circles. But this paper carries fundamental issues and questions very little of its own assumptions. It was such a severe letdown that prominent computer engineer and chief scientist for IBM's research wing, Grady Booch, weighed in on the affair. "This paper is an epic failure on every level: assumptions, process, data science, and ethical foundations," Booch said. "Bad science, all around."