Trauma

Therapy app responds to backlash over Travis Scott partnership

“It’s disheartening to see the way misinformation is spreading about us” in the wake of their Astroworld offer, says a rep for the controversial service BetterHelp.

When YouTubers first started to open up about burnout in 2018, it was BetterHelp that came to the rescue.

The company — which describes itself as “the world’s largest therapy platform,” with a mission to make mental health care “accessible, affordable, and convenient” connects users to licensed therapists, allowing them to video conference, call, and text chat with a counselor through its app. It seemed to see opportunity in the weariness of content creators.

BetterHelp partnered with popular YouTubers like Philip DeFranco, Shane Dawson, and Gabbie Hanna, sponsoring their videos and, in turn, garnering reviews from the creators. Then the YouTube community began discussing the app’s purportedly appalling service and what people perceived as its opportunistic relationship to the vlogger mental health crisis. What Polygon described as “a whirlwind of controversy” enveloped the company. Three years later, history is repeating itself.

“It’s disheartening to see the way misinformation is spreading about us.”

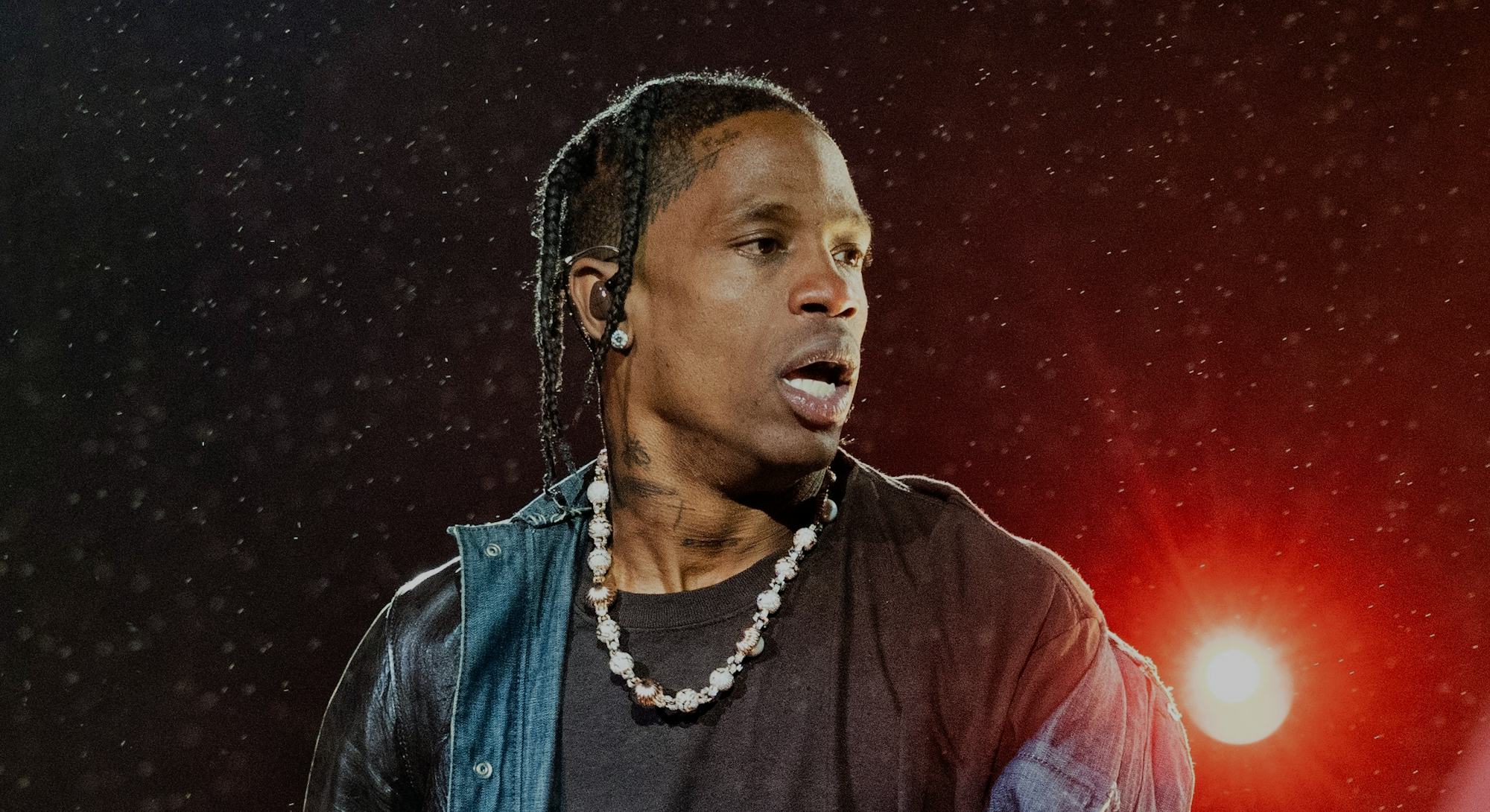

In the wake of the recent Astroworld tragedy, which claimed eight lives and left a further 23 hospitalized, headliner Travis Scott announced he was partnering with BetterHelp to offer festival attendees one month of free membership to the app.

This alliance between Scott and BetterHelp has led to a fresh outpouring of criticism on social media. Former users and psychology professionals alike have called BetterHelp inadequate, exploitative, and even damaging. Many on Twitter felt the partnership smacked of opportunism.

The company, which has previously partnered with Ariana Grande and Venus Williams, says it’s being treated unfairly. On its website, the mental health provider says that the therapy is being paid for by Scott’s youth foundation, Cactus Jack. It clarifies that Scott will not profit from the partnership. BetterHelp also denies that it offers poor care to its clients or that it sells user data for profit — the latter being a claim that a rival therapy service has been airing on TikTok.

“It's disheartening to see the way misinformation is spreading about us, but we're more saddened by the way this is hurting the perceptions of mental health care,” a company spokesperson tells Input. “Our goal has always been to normalize mental health by making therapy accessible. Coverage like this only hurts that greater cause.”

A publicist for Scott did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Poor reviews

Many are worried the “accessible” therapy offered by the organization will be inadequate for Astroworld survivors.

Among them is Jason, a 33-year-old former BetterHelp user from Illinois who asked that his last name not be used for privacy reasons. He tells Input that his BetterHelp counselor gave generic, googleable advice at a price point of $300 a month and seemed overstretched. “He admitted he was working with at least three other [therapy] services,” Jason says. “I got the sense he was balancing dozens of patients.”

He is also worried about the level of care BetterHelp offers its users. “You are limited to one live session a week, and the sessions are firmly cut off at 30 minutes,” says Jason, who says he canceled his BetterHelp subscription after his counselor fell asleep mid-session. “These people who experienced Astroworld need so much more help than that.”

Katherine, another former BetterHelp user who asked that Input withhold her real name, had an upsetting experience with her counselor, too. English was a second language for Katherine’s therapist, and it made communication difficult.

“As I gave her my history she just kind of said random platitudes, like ‘Okay’ and ‘Oh,’ until the session was over,” recalls Katherine, who is 30 and based in the Northeast. It had a negative impact on her mental health. “BetterHelp left me in a worse position than I started in. I felt like I was treated like a customer and not a patient.”

Her experience left her with doubts about the strict vetting process for therapists that BetterHelp promotes on its website. “I do not believe they’re being honest about their process, because I don’t believe my therapist would have passed an interview,” Katherine says. She shared screenshots with Input in which BetterHelp approached her directly after seeing her public complaints on Twitter. When Katherine asked for more information on the organization’s vetting process for therapists, BetterHelp stopped responding.

Nicole Froio, a 31-year-old writer and researcher from Brazil who used the app while living in Florida, thinks that BetterHelp’s partnership with Scott is highly suspect. “Any kind of commodification is unethical in capitalism,” says Froio. “But jumping on a tragedy that traumatized hundreds of people with the standard offer of a free month trial? It’s emblematic of the way mental health apps are being used in place of actual humane care.” (BetterHealth says on its site that it doesn’t regularly offer a free month of therapy, “only on specific occasions.”)

Froio says the app did not help her through her own trauma. She doubts it will help Astroworld survivors. “As someone with PTSD, the idea that a month of free therapy could even begin to address the amount of trauma the people at Astroworld suffered is laughable,” she says. “The victims of this tragedy need material and financial support, solidarity, and years of therapy.”

Experts agree. “The security and safety necessary for trauma therapy treatments to work cannot be attained over text message,” says Carolyn Michaels of Philadelphia. Michaels is a pre-licensed therapist who has been working as a counselor since 2015. ”Even with video sessions, a month is typically not enough time to complete the process. So offering a month of free therapy isn’t offering trauma treatment. It’s offering, at best, short-term support.”

Dr. Panagiota Korenis, associate professor of psychiatry at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York, believes that a month of therapy “might be,” enough to treat people who were “shaken up” by the event.

But she’s uncertain BetterHelp could support survivors with complex needs. “The drawback to this app is that they currently only treat conditions using therapy as the primary modality,” Korenis explains. “If someone needed medication management, those individuals would not be able to be connected to psychiatrists and would need to find an alternative provider.”

“These kids at Astroworld need advocates and intense therapy — and probably psychiatric help.”

BetterHealth defends its service. “With over 25,000 licensed therapists in our network, we have plenty of specialists who are well equipped to handle things like trauma and PTSD,” a spokesperson tells Input. “Therapy online is not always a good fit for all circumstances, but in cases where we are not equipped to help someone, we provide extensive resources to find in-person care.” (“Extended therapy support will be provided at no cost to those who need it,” according to a BetterHelp page updated today.)

While BetterHelp offers trauma specialists, it does not offer treatment for minors — which is a concern, given how many attendees of Astroworld were under 18. The festival’s website welcomed children to the event, and footage has since emerged of attendees as young as five. Nine-year-old victim Ezra Blount is in a medically induced coma, and John Hilgert, 14, and Brianna Rodriguez, 16, lost their lives.

BetterHelp’s spokesperson tells Input that minors as young as 13 “will be redirected to our teen therapy site, teencounseling.com” — which means the very youngest concertgoers would not be eligible for help. Those teenagers who do get a referral would be using a service with poor reviews and high price points.

Former BetterHelp users like Jason hope that, whatever happens, victims of Astroworld will get access to the care they deserve. He doesn’t think BetterHelp’s counselors will offer that. “These kids at Astroworld need advocates and intense therapy — and probably psychiatric help,” he says. “Not some guy to recommend a breathing-exercise app.”