Guerrilla marketing

Remembering the ‘Aqua Teen Hunger Force’ bomb scare that shut down Boston

Fifteen years ago, a movie PR stunt went horribly awry. For the first time, all the major players talk about the great Mooninite panic of 2007.

On the morning of Jan. 31, 2007, the executive vice president and general manager of the Cartoon Network, Jim Samples, was sitting in his office in the sprawling Turner Broadcasting Techwood Campus in midtown Atlanta.

It was a typically busy start to the workday, and he was in the middle of a closed-door meeting when his senior vice president of marketing, Dennis Adamovich, came flying in.

“Turn on CNN!” Adamovich said. “Quick!”

When Samples, then 43, flipped on his TV, he learned someone in Boston had reported an unidentified electronic device. Over the course of the day, first responders found almost 40 more just like it in Boston and neighboring Cambridge and Somerville. The panels were everywhere: above the entrance to an Allston comic book shop, next to the Gate C sign outside Fenway Park, clinging to the Longfellow Bridge.

But as Samples watched the initial coverage, he had no idea the havoc that was about to transpire. All he knew was this alleged “terrorist device” was part of the guerilla marketing materials for Aqua Teen Hunger Force Colon Movie Film for Theaters, a forthcoming movie based on the beloved short-form cartoon (about three roommates who happen to be anthropomorphic fast food treats) that aired on Adult Swim, Cartoon Network’s edgier evening programming block. And he had to tell someone.

Samples and Adamovich frantically dialed a number across town, attempting to reach the newsroom at CNN, another branch of the Turner Broadcasting family. “We were trying to say, ‘This is actually us — this is Turner, this is our show,’” Adamovich recalls. “It was just taking an exorbitant amount of time. And it was frustrating, because you couldn’t catch it fast enough.”

Indeed, the situation escalated quicker than you could repeat the title of the film the campaign was promoting. The War on Terror, launched in the wake of 9/11, dominated the headlines, and levels of paranoia remained high. So when Boston authorities were presented with a mysterious electronic object, they reacted decisively. Police closed the Longfellow and Boston University bridges, and the U.S. Coast Guard halted boat traffic on the Charles River. The Orange line shut down for more than an hour, as did the northbound side of I-93 and several main roads.

Commutes were thwarted, confusion reigned. If, like me, you were in the city that day, you might have heard the wails of ambulance sirens or the earthshaking blast of the bomb squad as they deracinated a device with a water cannon. My friend Jon Ryan, a fellow sophomore at Emerson College, was one of the unfortunate souls trapped underground on a full train. “I was super-pissed when I found out what the holdup was,” he says. “The fact that it took them an hour to be like, ‘Nah, it’s just a Lite-Brite’ was one of my first real ‘Your tax dollars at work’ moments.”

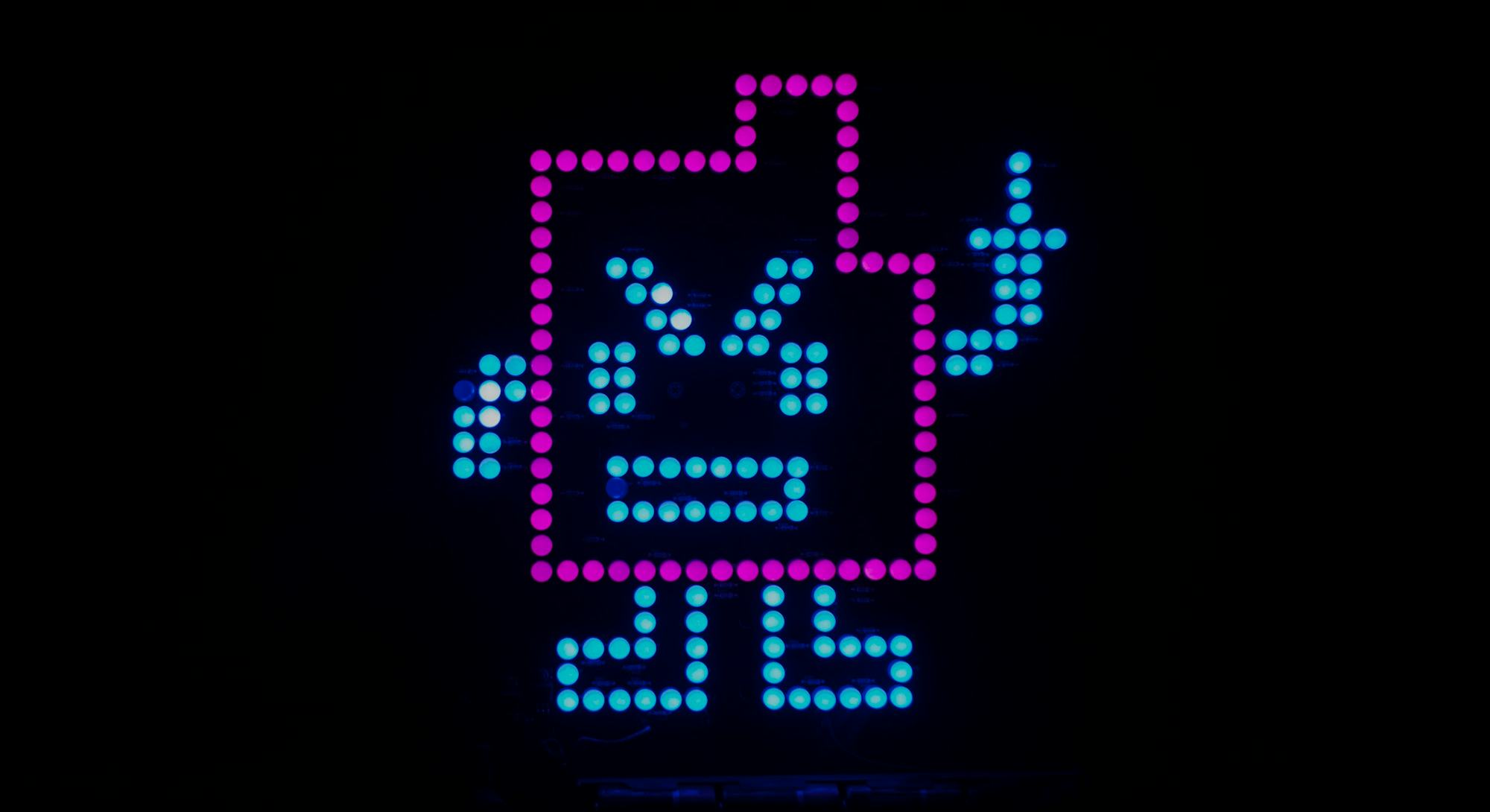

The devices that temporarily paralyzed Boston were black panels measuring around 14 inches tall by 11 inches wide. There were two versions: one was hot pink and blue, the other bright green and blue. Both featured 47 LED bulbs depicting cartoon figures with raised middle fingers: They were Aqua Teen characters named Err and Ignignokt, extraterrestrials known as Mooninites. Each device featured a full metal circuit board; with batteries, the whole thing weighed around two and a half pounds.

By mid-afternoon, Boston authorities concluded the panels posed no threat, and people began looking for someone to blame. Some criticized the authorities and the media for losing it over a cartoon character “shooting the bird,” as the Mooninites would say. Boston authorities blamed Turner for inciting a panic, wasting city resources, and engaging in “unconscionable behavior” post-9/11.

The Boston Mooninite panic — which took place almost exactly halfway between 9/11 and the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing — has gone down in the annals of history as the guerilla marketing initiative that brought a city to a standstill. (Samples and Adamovich are still sensitive about the incident being described as a “hoax,” as there was no intent to make anyone think the Mooninite devices were bombs. “This is not the kind of publicity we would ever seek,” Phil Kent, the chairman and CEO of Turner, said at the time.)

For those of us in Boston that day, the incident illustrated something of a generational divide. Depending on your age and level of pop-cultural literacy, you either believed the media and were understandably caught up in the panic, or recognized the characters and were bemused by the whole to-do. (“L-E-D. Not I-E-D. Get it?” a local blogger snarked.)

I happened to fall into the latter category. Naturally, so did Dave Wills, one of the two creators of the Aqua Teen series. “You see these videos of people in hazmat suits exploding this little Lite-Brite,” he says. “It’s a comical image.” However, given the serious tenor of the times, he adds, “you couldn’t make light of it.”

The arrests

Sam Ewen — the 37-year-old head of Interference Marketing, a well-renowned, New York–based firm specializing in guerilla advertising — was on his way back from an appointment in Maryland when he first realized something was amiss.

He had brought one of the Mooninite panels to the meeting to show it off, and as he stopped for a bite before boarding a train home to New York, he looked up at the TV in the Baja Fresh and was shocked to see that same panel staring back at him from CNN. “They were showing the removal of the first one,” he recalls. “And then subsequently having the bomb squad destroy it.”

The campaign was inspired by electronic graffiti, which had become popular within artist and activist communities. Cartoon Network hired Interference to incorporate the concept into a small interactive campaign to promote the ATHF film. What Interference came up with was essentially a scavenger hunt: The agency contracted freelancers in 10 major markets, including New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago, to hang devices in different locations. (Samples and Adamovich specifically remember being told by Interference’s team that they’d be placed in “stores and bars.”)

The campaign was designed to appeal, almost exclusively, to fans of the ATHF series. The target demographic was so niche, in fact, that Interference’s team selected the Mooninites, secondary characters in the series. (“The first few hours of news coverage, they kept thinking it was SpongeBob,” says Matt Maiellaro, ATHF’s other creator. “Nobody knew what it was.”)

Ewen says the agency examined public-defacement statutes in each city, and determined that the devices, which clung to metal surfaces courtesy of rare-earth magnets, qualified as magnetic litter, which left it up to the cities as to whether they should be removed. Contractors were instructed to hang the devices in central locations around their cities, but in high enough spots that fans would have to exert themselves to secure one. “It was ephemeral media that was meant to be taken,” Ewen says.

Freelancers completed the work in mid-January under the cover of darkness, using long extension poles retrofitted with a hook. For their work, they were paid $300 each. In Boston, the team was visual artist Peter Zebbler Berdovsky (better known as Zebbler, his adopted middle name and artist moniker), then 27, and Sean Stevens, 28, a friend from the Boston tech-art scene.

For the first few weeks after the devices were installed, everything went as planned. Then, on Jan. 31, 2007 at 8:05 a.m., a Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority employee saw a black box with exposed wires attached to a steel girder by the Sullivan Square train stop and reported it to the authorities.

Zebbler was taken into custody at his host family’s house that evening. (He believes the police tracked him using the fingerprints he provided when immigrating to the U.S. from Belarus.) He called Stevens to let him know of the arrest, but the police took the phone and asked to interview Stevens, too. “I told them I would have to cancel my dinner plans, but since it seemed important to them, I would do that,” Stevens tells Input in an email. He was also arrested that night.

A recent art school graduate and aspiring visual artist with dreadlocks down his back, Zebbler was living paycheck to paycheck, and accepting any freelance gig that came his way. And for this job, he went all out, bringing in his friend and upstairs neighbor, Dana Seaver, to help document the panel-hanging progress, which Zebbler had posted online well before anyone panicked.

Even after he and Stevens were charged with planting a hoax device and disorderly conduct, Zebbler felt confident reason would prevail. That confidence was tested when Boston’s then mayor, Tom Menino, threatened them with multiple years in jail for every device they put in place, a sentence that would have left them imprisoned for over 100 years.

After making bail, the two men held a press conference in which they waxed poetic about the merits of ’70s haircuts. (Both were advised by their lawyers, who were paid for by Interference, not to comment publicly on the situation.) The only query the pair willingly answered came from the reporter who asked if they were scared they would have their hair cut in prison. “Whatever happens, I feel like my hair is safe at the moment,” Zebbler said, tugging on his dreadlocks.

“We felt that by inserting a hearty dose of the absurd, the public would wake up to the fact that all of this was ridiculous,” Zebbler tells Input via email.

After the incident, Zebbler experienced a brief brush with infamy. His distinctive look didn’t lend well to blending in, and so he became known in Boston as “that guy.” Everywhere he went, people gawked. His email was overrun with scams and interview offers. But it was still 2007, and the instant celebrity-to-influencer pipeline had not yet been created. Zebbler struggled to redirect the public attention away from the scandal and toward his visual art.

Zebbler and Stevens were offered a plea deal, which Stevens felt pressured to take. “I was told if I didn’t accept the plea, Zebbler would not be offered it either,” Stevens recalls. “He’d lose his U.S. political asylum and be sent back to Belarus — essentially an active warzone.”

They took the plea deal. In exchange for community service, their case was reduced to a nolle prosequi, meaning the prosecution simply stopped pursuing the charges. “In the end, it took half a year out of my life,” Zebbler says.

Meanwhile, there was no legal action in the other nine cities where the panels had been placed. In Los Angeles, police refused to open an investigation, stating, “There’s no reason to believe a crime has occurred.” A sheriff’s spokesman in Seattle agreed: “To us, they’re so obviously not suspicious.” Other parts of the country took a slightly harder line: Chicago’s police superintendent said the panels “could have easily been mistaken for a bomb,” and Philadelphia’s mayor called the idea a “stupid, regrettable decision.”

The fallout

Less than a week after the incident, Turner agreed to pay $2 million in recompense; $1 million went to Massachusetts cities and state agencies, and the other million was set aside to support programs focusing on homeland and community security, and safety education. Turner, Adamovich says, handled the fallout “magnificently” and “really took accountability.”

That accountability included a trip to Boston during which Adamovich and other Turner execs personally apologized to the mayor and his cabinet; later, the company created a three-year, $500,000 initiative to teach broadcasting to Boston public school students.

Turner was determined to own its involvement in the crisis — and ultimately that meant a blood sacrifice would have to be made.

Samples worked late into the night on January 31, and around midnight, he joined the president of Turner Entertainment Group, Mark Lazarus, at the nearby Omni Hotel for a drink. As the month changed, he told his boss, “I understand you may need to fire someone over this, and if you need me to resign, I will do it.” His offer was waved off.

In the following days, conversations apparently were occurring among the upper echelons of Turner and its parent company, Time Warner. Samples says he’ll never know who made the decision, but in the week following the incident, he was asked to submit his resignation. His departure was announced on February 9, three days before his 44th birthday.

“Things just happen sometimes,” Samples says. “And when they do and it goes horribly wrong, as the leader of the organization you could pay the ultimate price for that, which I did.” He adds, “I felt a deep sense of responsibility. I was worried about my team members getting fired. And I was not willing to point fingers at individuals.”

The first thing Jim Samples did after submitting his resignation was drive to REI to purchase a pair of boots. Then he drove home, put the boots on the table, and told his wife he was going for a very long hike. When Samples departed Cartoon Network, he left with a binder of more than 1,500 pages of press clippings covering the Mooninite scare story, a gift from his team created at his request. Three months later, he embarked on a 10-week, 1,100-mile solo walk across France and Spain. As he walked, he reflected on his 13 years working at Turner and wondered what he could have done differently.

The Boston situation didn’t keep the Cartoon Network from squeezing in an April Fool’s Day joke related to the film. The network promised to air a sneak preview of the full movie on Adult Swim, a week and a half before the theatrical release. And it did — except it played the majority of the film with no sound, squished into the bottom left-hand corner of the screen as the network’s regularly scheduled programming aired.

The ATHF film finally premiered later that month without further incident, making $5.5 million dollars at the domestic box office, more than seven times the movie’s $750,000 production budget.

Maiellaro and Willis had no affiliation with the campaign, but they were more than happy to embrace the unexpected publicity. “We were ready to write a script where the Mooninites are like, ‘We’ve taken you down, Boston,’” says Willis. “‘Now, Cleveland, you’re next!’”

That script never materialized, but a parody episode called “Boston” featuring Paul F. Tompkins in the role of a police officer was slated as the show’s 2008 premiere and 69th (nice) overall episode. The writers took several stabs at the story, but suspected the higher-ups never liked their take, because the episode was eventually scrapped.

A rough cut leaked online on Jan. 31, 2015. It follows the Aqua Teens as they head to Boston to drum up publicity for an auction, only to be run out of the city after Meatwad, the gullible ball of ground mystery meat, is mistaken for a bomb. Both Maiellaro and Willis deny responsibility for the leak.

The legacy

Today, the only person I could track down with one of the Boston Mooninites is Tito Bottitta. As a 26-year-old digital design director for the Boston Globe, Bottitta spent January 31 pouring over the photos Zebbler posted, creating a map of the devices for the Globe’s website. That night, he retraced Zebbler and Steven’s steps through the city, snagging a Mooninite of his own. (Ewen suspects any other panels that survived detonation are still at “some officer’s house.”)

Bottitta wasn’t the only person to find one in Boston, though: A Northeastern student — and friend of Zebbler’s — discovered a panel outside the Hess gas station sign on Commonwealth Ave. He attempted to sell it on eBay in hopes of paying off his student loans, but the auction was shut down for “encouraging illegal activity.” (If you’re interested in owning a light-up Mooninite of your own, you’re in luck: Replicas of the device are available on Etsy for around $350.)

As for the folks most directly involved in the crisis? They’re largely doing okay for themselves 15 years on.

Soon after completing his very long hike, Samples accepted a position with Scripps as the President of HGTV, which later involved a move to Poland to head up its international division. He has since retired and hopes to set up an artist-in-residence program on his farm in Tennessee.

After a 15-year-long tenure at Turner, Adamovich moved to a new role as the CEO of the Chick-fil-A College Football Hall of Fame in 2016. He now works as the chief development officer of Times Square Live Media Enterprises, a Manhattan-based broadcast production and distribution company.

Zebbler felt aftershocks from his involvement in the campaign years later when he applied for citizenship and found his case held in review for a “very scary” year. Eventually his application went through, and on the 10th anniversary of the incident, he posted on Facebook, “I was a refugee. Thanks for not kicking me out, guys.”

Today, Zebbler still lives in Boston. He’s a touring visual and performing artist and an assistant professor at Berklee College of Music. He and the city are on much better terms: In 2013, he was asked to create a light show as part of their First Night celebration. (“We’re a forgiving city,” the late Mayor Menino told the Boston Herald.)

Stevens continued to create interactive art pieces. For a few years, he “accidentally became a teacher” and eventually moved to San Francisco. He’s since created a nonprofit space for artists and creators there called Momentum. In November 2018, he was diagnosed with Stage IV cancer, which he was told has a 17 percent survival rate.

Ewen still works in marketing, and while his firm lost both money and clients in the fallout, he says the reputation it earned as some of the most “daring marketers around” didn’t hurt his career in the long run. Guerilla marketing, however, didn’t fare as well. “There are now protocols in place so this thing will never happen,” says Adamovich. “Systems have changed. The way we market has changed.”

What endures is the memory of the Boston Mooninite Panic, gleaming like Lite-Brites in the minds of those who planned and executed it and those who were in the city that day. And, of course, the minds of the ATHF creators themselves. “I’ll go on record as saying I still think it was a good idea,” says Willis. “Just maybe not on bridges.”

ATHF continued to air for another eight years after the incident, making it one of Adult Swim’s longest-running shows. The series was canceled — against fan and creator wishes — during production on the 11th season, and the series finale ran on Aug. 30, 2015.

Maiellaro and Willis currently are working on a new ATHF movie, which will come out later this year. As for how it will be marketed? “There may be another viral campaign,” Maiellaro jokes.

Additional reporting contributed by Kasey Fielding.