Features

The secret 'second job' for Geek Squad's women: fighting off sexual harassment

The tech retailer has been hit with several lawsuits in recent years from employees who allege workplace abuses.

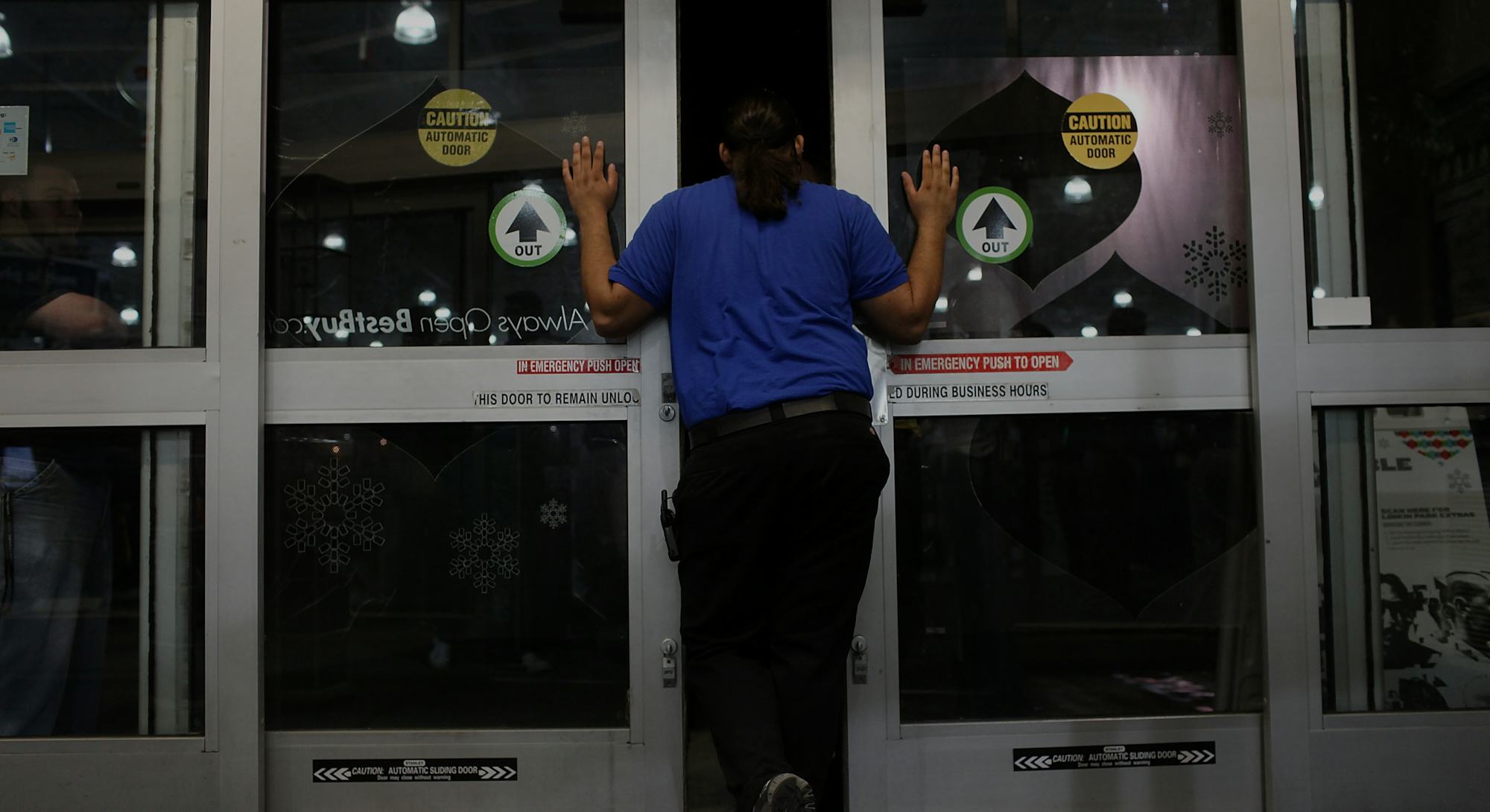

Customers never came to visit the Geek Squad counter at Best Buy because they were having a good day. Sarah Tremblay, who worked at two store locations for the multibillion-dollar corporate giant from 2014 to 2018, remembers verbal abuse and harassment as customers offloaded their frustrations to employees. But what really made her uncomfortable was when that anger slipped into sexual harassment — which it often did.

Sexual harassment was common, faced primarily by female employees working at Best Buy. But Best Buy, she alleges, didn’t value the labor of its female employees enough to do much about it.

“Nobody is coming because everything is going right for them. You’re usually going to have to deliver some sort of bad news and there’s a price tag that comes with it, and people are usually entitled to getting their stuff fixed fast and free. And that’s just not how capitalism works,” Tremblay said.

“Just being a female Geek Squad agent is a second job on top of being a regular agent,” she said. “Because you’re having to constantly manage those customer interactions when they get weird [and become sexual harassment].”

Tremblay recently filed a lawsuit with New York’s state court against Best Buy for sexual harassment and retaliation. Tremblay was fired from her job in late 2018 for, according to the company, excluding some men from participating in online customer surveys — men who Tremblay says harassed her. She alleges the dismissal, which happened without warning and on the heels of a promotion, was punishment for pursuing her sexual harassment complaint within the company. Best Buy did not respond to requests for comment on sexual harassment allegations at the company’s premises.

“I get sexually harassed by men almost every shift.”

Tremblay is not the only female-identifying employee alleging that they have encountered sexual harassment in the technology corporation, which has 977 branches in the United States. Natasha*, a 20-year-old college student who worked part-time at a Best Buy store in the Chicago area before being furloughed because of the pandemic, said sexual harassment at her workplace is almost mundane.

“I’ve been harassed by managers and customers both,” Natasha*, who recently quit her job, alleges. “I had a customer call me a ‘skank ass hoe’ because her item wasn’t ready for store pickup. I get sexually harassed by men almost every shift. A customer once asked me how old I was, and when I said 20, he said, ‘You must be tight as hell.’”

While Best Buy markets itself as an empowering company for women, run by a female CEO and appearing on Forbes’ top 10 best workplaces for women, numerous sexual harassment lawsuits have been filed against it in the past few years. In April 2020, Alyssa Brooke Shoun, who was 16 years old when she started working at Best Buy in Maryland in 2017, filed a lawsuit alleging continuous sexual harassment from coworkers, which management allowed to flourish unchecked.

Similarly, in 2016, Ibry Batista, a Best Buy employee who worked in Geek Squad at a New York City store, sued the company for sexual and racial harassment. Batista alleged racist jokes were sent in the employee GroupMe chat and that she faced racialized comments from her supervisor.

Earlier this year, Erika Bazemore, a wireless sales consultant at Best Buy, unsuccessfully sued the company after her coworker allegedly made a “racist and sexually-charged joke” employing the N-word. The incident made Bazemore feel like other “coworkers [were] looking at her breasts,” and caused her lasting depression and weight loss, according to the judge’s opinion. Anne Creel, the white coworker who allegedly made the offensive comment, was disciplined but not fired.

A tech problem

The problem female employees face at Best Buy speaks to a larger problem in the tech space in general. Misogyny remains a persistent problem in gaming communities dominated by men, which culminated in the infamous #Gamergate scandal in 2014 where female gamers faced a vitriolic pile-on from men suspicious of women taking up space in a traditionally-male pastime. According to business journalist Emily Chang, the gender disparity in Silicon Valley outranks Wall Street, and companies helmed by women obtain just 2 percent in venture capital funding.

Shania Harry, a database specialist who worked with Tremblay on Geek Squad, never experienced any blatant harassment at her job at the tech retailer but felt like she wasn’t taken seriously as a woman and therefore couldn’t move up in the workplace.

“There definitely was an environment of sexism, because I felt I was more experienced than some of the guys there but when it came to doing more difficult tasks, they’d just be like, no, you can’t do that,” Harry, 25, said. “[Based on my experience, women] weren’t given tasks outside of speaking to customers. We weren’t given real work related to repairs or anything technical really. They just wanted you to stand and talk to the customers.”

In 2011, Best Buy settled a class-action lawsuit alleging sexist and racial discrimination at a store in Oakland, California. The company paid $200,000 in damages and committed to making a better workplace environment for employees, which prioritized diversity and implementing policies that minimized harassment or retaliation. In Best Buy’s 2019 Code of Business Ethics, employees are encouraged to put a stop to harassment if they see it.

Best Buy is not the only tech company to be sued for sexual harassment. In 2017, numerous women came forward in Silicon Valley recounting graphic instances of workplace sexual harassment. The reckoning caused major investors to resign and led to 20,000 Google employees walking out from offices in protest of multimillion-dollar exit packages given to executives accused of harassment. Recently, Google implemented a new policy forbidding romantic relationships between bosses and employees, and made arbitration optional for workers filing complaints of sexual harassment.

“He’s a customer and you will get in trouble.”

In 2018, the Center for American Progress reported that more than 25 percent of sexual harassment charges filed with the government came from service workers, a job description often occupied by women. “Sexual harassment is a form of dominance and bullying. People do it because it feels good to belittle somebody else,” Susan Crumiller, an attorney who represents Tremblay, said. “So retail and service workers are particularly vulnerable.”

That same year, Tremblay was unexpectedly groped by a client. “A guy wrapped his arms around my waist,” she said. “And I froze in that moment because that’s what your body does, you just freeze. My brain was like, you should punch him. And the other half of my brain was like, he’s a customer and you will get in trouble.”

It's that principle that prevented her from resisting harassment, and one that abusers so often exploit. In the service industry, there's only one credo to abide by: “The customer is always right.”