Features

Labels don’t make rap stars anymore. Digital beat traders do.

The rise of sites like BeatStars and TrakTrain have changed the way the music business works forever.

Before the internet, even superstar producers like Dr. Dre went to extreme lengths just to get their beats heard.

The story goes that for Dr. Dre’s track, “Ask Yourself A Question,” to land on Kurupt’s album, the instrumental had to be physically flown on a personal jet overnight. Today, producers don’t even have to send beats by email — they have access to tools like BeatStars, which have made it painless and profitable for producers to “lease” a beat to several artists at once for as low as $20 a license, cutting the middleman out of the process. According to Abe Batshon, CEO of BeatStars, some producers have generated thousands of dollars off the repeated licensing of a single instrumental.

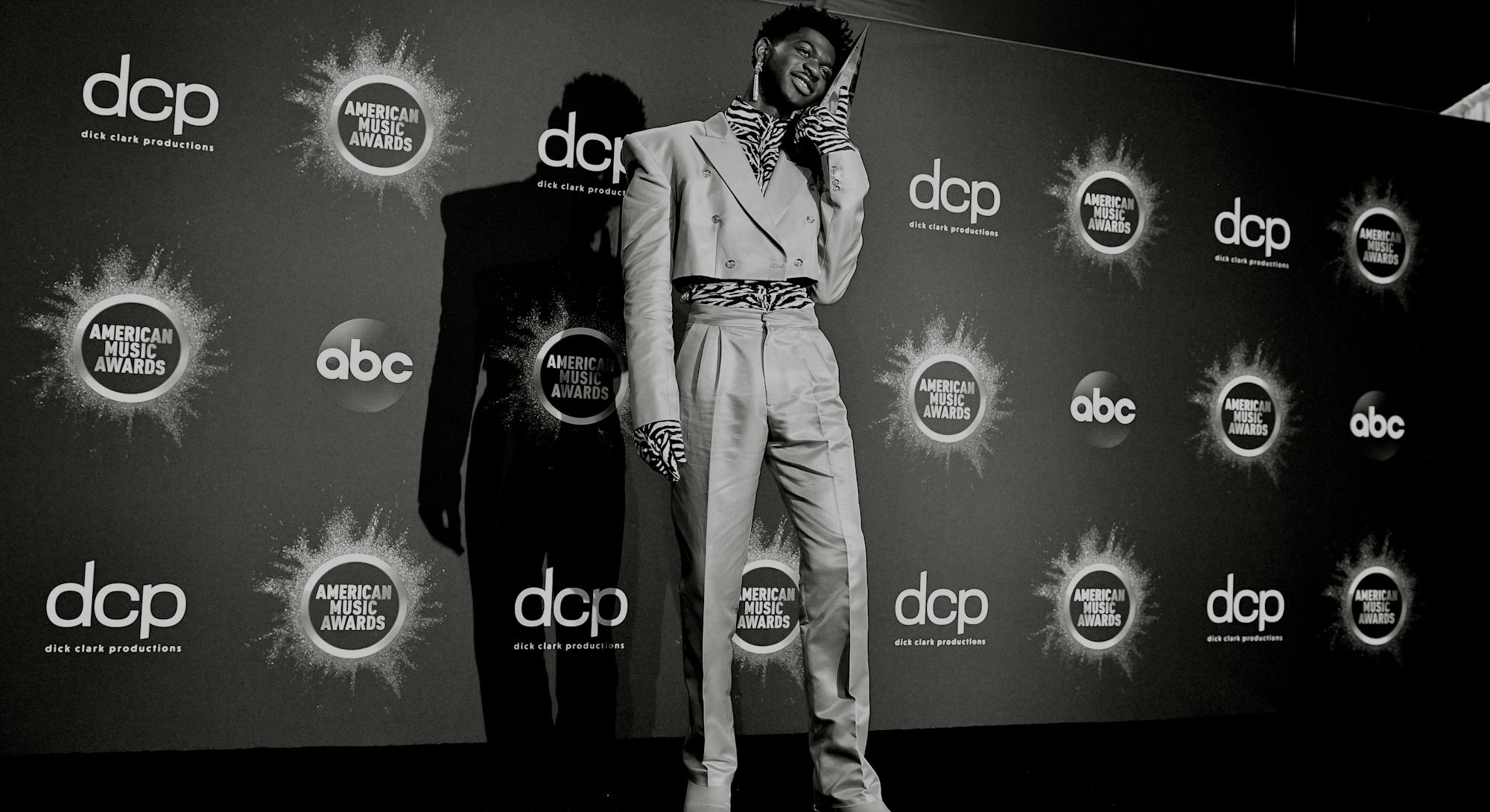

Since launching in 2008, BeatStars has ballooned into the world’s most successful beat marketplace, boasting nearly 2 million active users. The most notable is Lil Nas X, who famously purchased the instrumental for his No. 1 hit “Old Town Road'' from Young Kio, a producer from The Netherlands, through the site. The mobile app alone has a million users.

“Our platform was the first to provide artists the ability to download high-quality studio files, known as ‘stems,’ and then automate the entire licensing process on behalf of producers,” says Batshon. Yet every industry Goliath has a David, or 10. While BeatStars has grown into a powerhouse, even recently inking a deal with Sony Records, other platforms like TrakTrain, founded in 2013, have entered the market and differentiated themselves in the community through an unconventional model: invite-only.

“Invitation-only makes us different from our competitors and the invitation aspect of TrakTrain provides a filtration aspect that ultimately leads to TrakTrain having a reputation as a place of good music,” Tree Aiko, the CEO of TrakTrain who goes by an alias, told Input. “Artists come here first because it's easy to find new, quality beats. And for producers, when people get the request approved by an invite-code — they get a certain feeling from it.”

Niche Appeal

Despite the size of BeatStars — over 500,000 members since 2018, according to Vulture — Tree says that TrakTrain came in response to another site, called SoundClick, which Bryson Tiller name-dropped on the track “For However Long” and which Soulja Boy purportedly popularized. SoundClick enabled artists to upload free MP3s to their page.

In 2013 when the platform launched, each music site already had its own niche. Bandcamp was for indie artists, SoundClick was akin to Facebook for musicians, and BeatStars was a general marketplace for hip-hop, rap, pop, and R&B beats. TrakTrain branded itself with its invite-only model as a community of the elite. Although invite-only platforms have been around for years — the exclusive dating site, The League, boasts a 75K person waiting list — TrakTrain was the first to bring this idea to the music industry. To add to the intrigue, Tree created another alias, “Sayatoshi,” becoming the mysterious owner who spoke with prospective producers who applied to join the platform. Since then, TrakTrain has regularly received over 100 requests a day.

The main criteria to determine who is accepted to TrakTrain, Tree says, depends on the professional quality of their “mixing,” the behind-the-scenes process by which multiple sounds are combined into one or more channels. The process isn’t unreasonably rigorous, at least Tree doesn’t think so, and producers who are accepted to TrakTrain receive 100 percent of the proceeds from each sale after paying $9.99 for the opportunity to post 100 tracks. By 2016, the plan to cast TrakTrain as an elusive yet successful upstart platform was no longer as out-there as it first seemed. The site had amassed nearly 40,000 registered active producers.

Yet Tree was keeping another secret, one that likely played a large part in this early success: besides running TrakTrain, he also had a successful YouTube channel to which he uploaded beats, too. According to Tree, the channel was popular, and he soon got to know other producers who were uploading their beats to YouTube as a way of driving traffic to their BeatStars or SoundClick page. By leveraging Tree’s network of internet producers — and by plugging the service to his YouTube followers — TrakTrain grew through word-of-mouth.

Soon, vocalists like Joyner Lucas, Scarlxrd, and Megan Thee Stallion began purchasing beats off the site, along with producers like Fish Narc, Horse Head, and Yung Cortex, the latter affiliated with the iconic late SoundCloud megastar, Lil Peep. The bigger the underground SoundCloud movement got, growing from a fringe movement to being reported on in The New York Times and Rolling Stone, the larger TrakTrain became. To this day, Tree says he has never spent a dollar on advertising. “I'm not sure how it happened but it seems like the ‘SoundCloud producer scene’ aligned itself with TrakTrain,” says producer Fantasy Camp, a frequent collaborator of Lil Peep’s former collective, GothBoiClique.

“[BeatStars] was kind of the first DIY website tailored to music creators.”

A Google Trends chart (note: these aren’t always accurate) shows that up until the winter of 2016, TrakTrain was making some headway towards catching up with BeatStars. The two were almost neck and neck until BeatStars took off with the relaunch of the Pro Page, an innovative move which allowed it to pull ahead in the industry.

“It was kind of like the first DIY website creator tailored to music creators to sell beats, memberships, kits, services, done in an out-of-the-box package white-labeled for each producer, and the first product of its kind,” says Batshon. “We had a previous version but the second version was a reintroduction with new customization, features, and modern design and the producer community really gravitated towards it.”

Today, it is still the best-selling product in the history of the digital music industry, and this month earned $100M in total revenue for creators. The Pro Page relaunch also received a flurry of media mentions from VICE, Entrepreneur, and others, culminating in it becoming the first beat site to become verified on Twitter. Suddenly, TrakTrain was again scrambling to keep up — and then the site was hacked.

“I was with a newborn at home and it sucked. TrakTrain was the only thing I had, so the temporary fall of the site crushed me,” Tree says. As soon as the site went down, TrakTrain tweeted about what had happened and pleaded to its followers for assistance. The tweet received nearly 50,000 impressions, according to Tree, and eventually, a user based in Eastern Russia asked for the password to the site to bring it online. Tree reluctantly took the risk — and it paid off. The user, J., who wishes to remain anonymous, mentioned he had a basic proficiency in software engineering and was willing to try to bring the site back online. “The music industry can be a tough place to be, and it was huge for me to have anonymous people reaching out to bring us back, I got really emotional over it,” Tree says.

By the end of the night, the site was restored and Tree was ready for another gamble. After meeting with a design firm renowned for its work, Tree emptied his life savings and eagerly waited for the initiative, dubbed “TrakTrain 2.0,” to kick off. “Everything was ready to go, man,” Tree says over the phone, “I was hyped.”

“It was a scenario I never thought could happen.”

But after a few months, when TrakTrain 2.0 should have been nearing launch, Tree received more bad news: his contractors weren’t close to finishing. In fact, they hadn’t even started. “It was a scenario I never thought could happen,” he says, “On one hand, I’m telling my community the new features are coming — all the while I’ve just learned the opposite. It was terrible.”

In a fury, Tree asked the developers to send him the code so he could review their work. He then sent it to his compatriot in Eastern Russia to get his opinion on their work. After J. reviewed the code, he informed Tree that it was completely useless. Stunned, Tree cut ties with the organization and instead asked J. to become his partner in exchange for helping lead the development of the site. Within six months, TrakTrain 2.0 was finished by Tree’s new partner, ahead of schedule and under budget, and an improved version of the platform was back online — this time with WAV file sharing, a key asset producers were clamoring for.

BeatStars, as well, had its own documented trouble with hackers the following year, in 2018, when a hacker tried to wipe its audio files. Despite the hackers managing to deface the site, it was back up and running quickly. And luckily, no content was lost.

Today, both platforms are reporting record growth and a host of new competitors — Soundgine, Soundee, and AirBit, the new incarnation of MyFlashStore — have joined the party. TrakTrain has resumed the strong growth trajectory that it was on prior to the hack, with nearly 100K registered users. While it’s not enough to compete with BeatStars, which is doing 10 times TrakTrain’s traffic, the platform isn’t an up-and-comer anymore. “Right now is the biggest we’ve ever been by far, COVID has really led to an uptick in users,” Tree says. “The growth we are seeing is crazy.”

For now, at least, the outlook for the entire industry is bright. In 2019 alone, music streams across U.S. platforms like YouTube, Amazon Music, and Spotify topped 1 trillion, and producers today have an array of tools on their hands — from digital marketplaces like BeatStars and TrakTrain to downloadable DAWs like Fruity Loops or Ableton — that their predecessors could only dream of. They aren’t married to a single platform, either; there is significant overlap between the communities of each. Because at the end of the day, as a result of innovators like BeatStars and TrakTrain, the entire music industry is winning.