I just finished reading an oddly named book by someone you’ve probably never heard of – I loved it so much I’m writing this site’s first book review.

Ken Kocienda is a talented developer. He’s also a lucky one: he worked at Apple during the years when the Mac was reborn and the iPhone was created.

If you’ve ever opened the web browser in your pocket or typed a text message on a piece of glass, you’ve used his seminal work. Ken was directly responsible for two important parts of the original iPhone: a fast and efficient web framework and a keyboard that was both virtual and predictive.

Ken is also a great storyteller. His experiences during these formative years provide great material for this narrative. But more importantly, he extracts lessons from these tales that can be applied to our own efforts.

In short, Creative Selection is a study on how great products evolve that inspires the reader.

I first learned of Ken’s work during a presentation at WWDC 2014. A Strategy for Great Work showed that in addition to doing interesting things, he also took the time for introspection and learning from the work. I immediately followed him on Twitter and eventually discovered our mutual admiration! (That, in turn, led to the advanced copy I’m reviewing today.)

This talk, along with the ones that preceded it, feel like a formative process for the chapters of the book. The video linked above will give you a very good idea for the tone of his latest work, but there’s also an important difference.

Ken no longer works at Apple.

The end of presentation in 2014 alludes to this situation: not being able to talk about certain things is a fact of life in Cupertino.

I found Ken’s new freedom most intriguing when he focused on other people’s contributions to the secret projects. Every developer knows that a success involves many different talents and personalities. And with Apple’s penchant for secrecy, we never hear about these team interactions.

The collaboration between Steve Jobs and Jony Ive is not only well known, it’s well understood. I think this is because industrial design is much more concrete and easier to interpret in the formative stages.

Steve had another important collaborator, but that relationship isn’t as well understood. Creating software requires abstract decisions and a more opaque process. How do you make a button on a piece of glass?

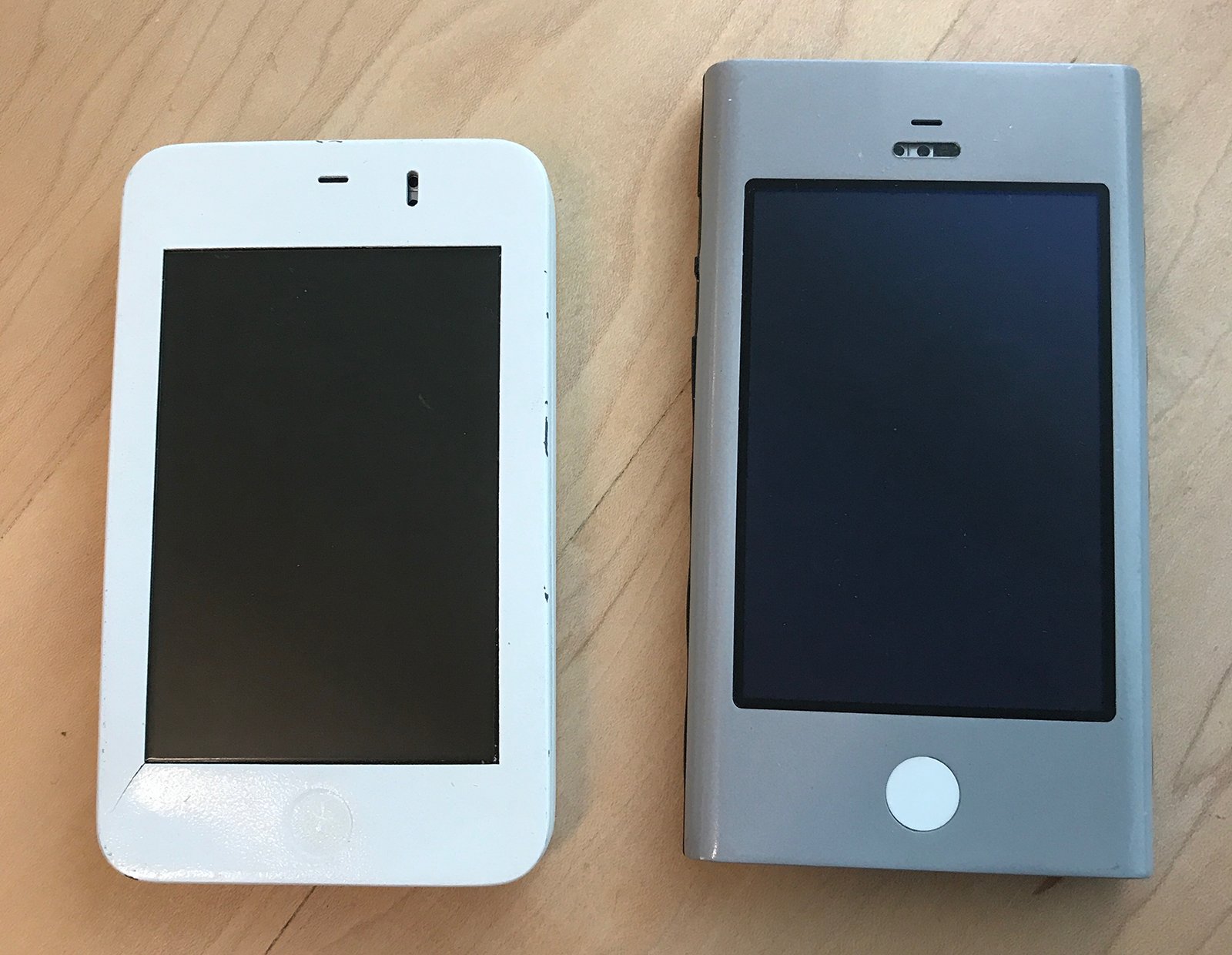

When you look at the Wallabies from Ken’s desk, you can see where the hardware is headed:

When you think about what was on those screens, things get more complicated.

This book changed my view of Scott Forstall because it gave context to his work. Ken’s account breaks down the approach and shows how important Scott’s leadership was to Apple’s success.

Having Steve Jobs as a boss for your entire professional career would not be easy, but Scott handled it with great success. Even when that powerful mentor was asking for skeuomorphism.

The hardware would be lesser without Jony, and Ken shows that the software would be lesser without Scott.

If you’re a developer, you’ll find some passages a little slow going. That’s because you know too much :-)

As a great storyteller, Ken endeavors to make the topic as widely understood as possible. To achieve this he turns to analogies in cooking, sports, and the movies while describing the process of creating software.

While we may not need this high-level view, there is an important group that will benefit: our families. If you’re like me, you’ve struggled to explain what you do at that keyboard all day.

We all love our iPads and Kindles for reading, but I’m really glad I have a printed copy of the book to share with the people I love.

I’ve avoided spoilers in this review, but I’ll end with one story that touched me. When asked about the most important thing in development, I always answer with one word: empathy.

Ken links this concept, along with the combination of good taste, the philosophy of Immanuel Kant, and a discussion of atoms by Richard Feynman, all while explaining the choice of a QWERTY keyboard layout.

These complex factors enable a personal connection between people. Imagine being the developer whose choices led to the ability to send a quick message saying “Just landed.” Informing a loved one of your safe arrival transcends the importance of any line of code.

That is work to be proud of and we’re lucky Ken has taken the time to share it with us all.